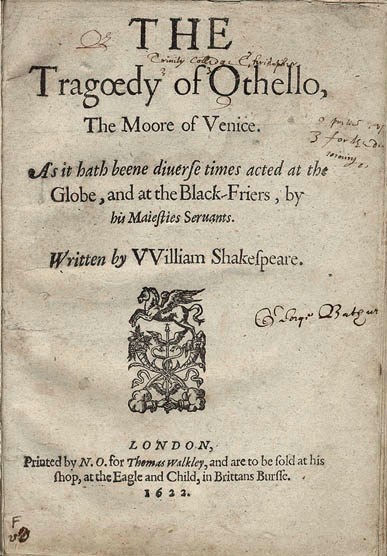

In 1603, William Shakespeare wrote The Tragedy of Othello, the Moor of Venice, often shortened to Othello. The play follows the life of a Moorish military commander, in love with the tender Desdemona, as he pursues power. In this pursuit, he is surrounded by a group of people, also pursuing power, who cannot tolerate seeing Othello make an unlikely social and political ascent. Iago, the most cunning of his supporters, decides to use the most lethal of weapons: doubt.

Iago plants the idea in Othello’s mind that Desdemona is betraying him with one of his most loyal supporters, Cassio. Othello, blinded by jealousy, is unable to see the truth and believes only what is apparent: that a morally corrupt woman like Desdemona who has betrayed her own father will, of course, betray him too. The narrative fits. The visible, the material takes over the invisible, the spiritual. Only what can be seen or perceived becomes the whole truth. In the end, Othello murders Desdemona, believing that he is doing the morally right thing by punishing the corrupt adulterous woman. When Emilia, after the murder has already taken place, exposes Iago, Othello realises what he has done. He unsuccessfully tries to kill Iago before committing suicide himself.

Every time I read the play, I think about the murky borders between the truth and narratives. The person and its silhouette.

Truth, to me, seems like salmon we cannot catch. We only have narratives that we either believe or don’t. In that, we are all Othello, sitting next to a murdered Desdemona.